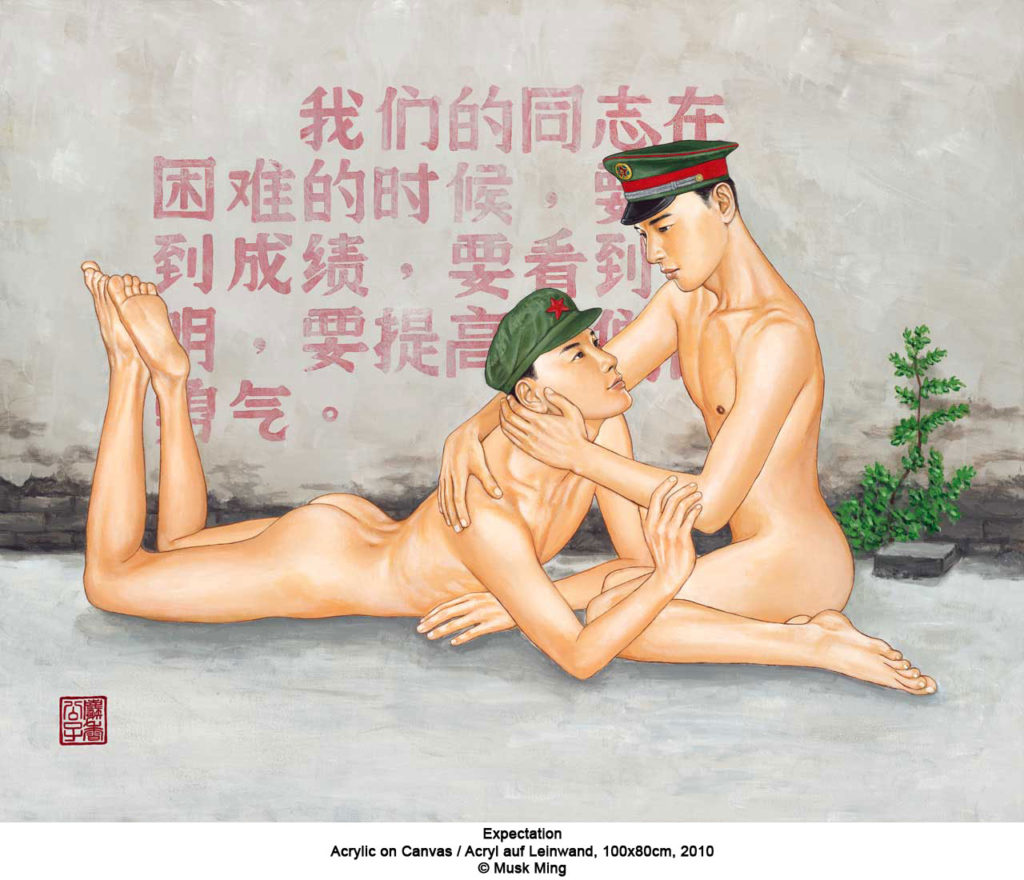

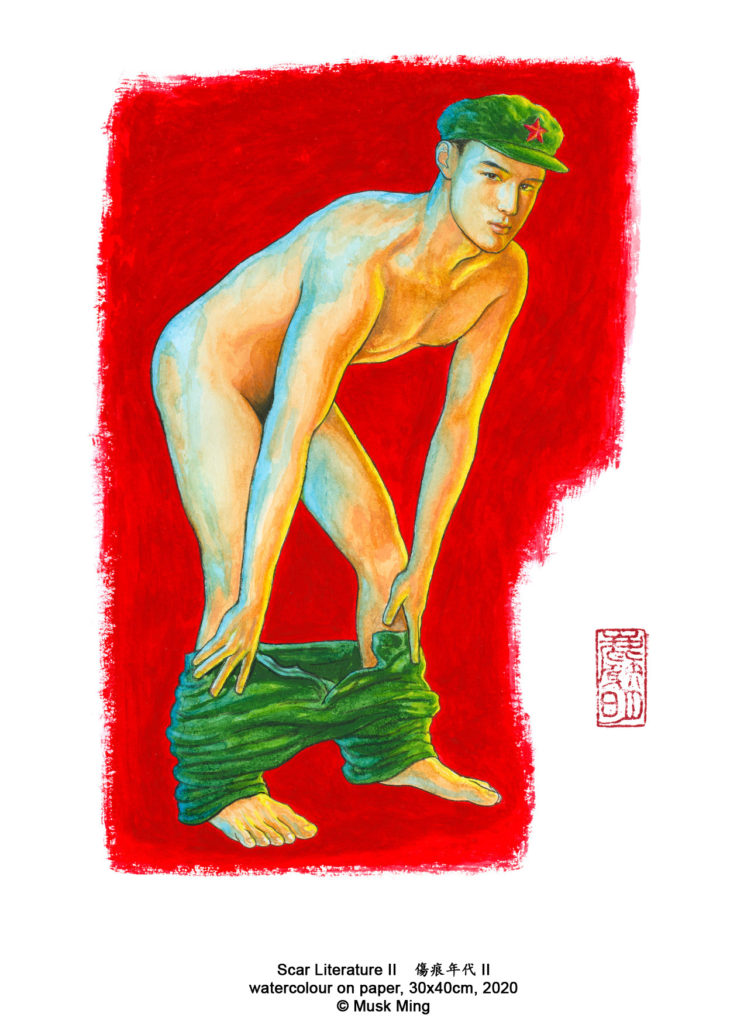

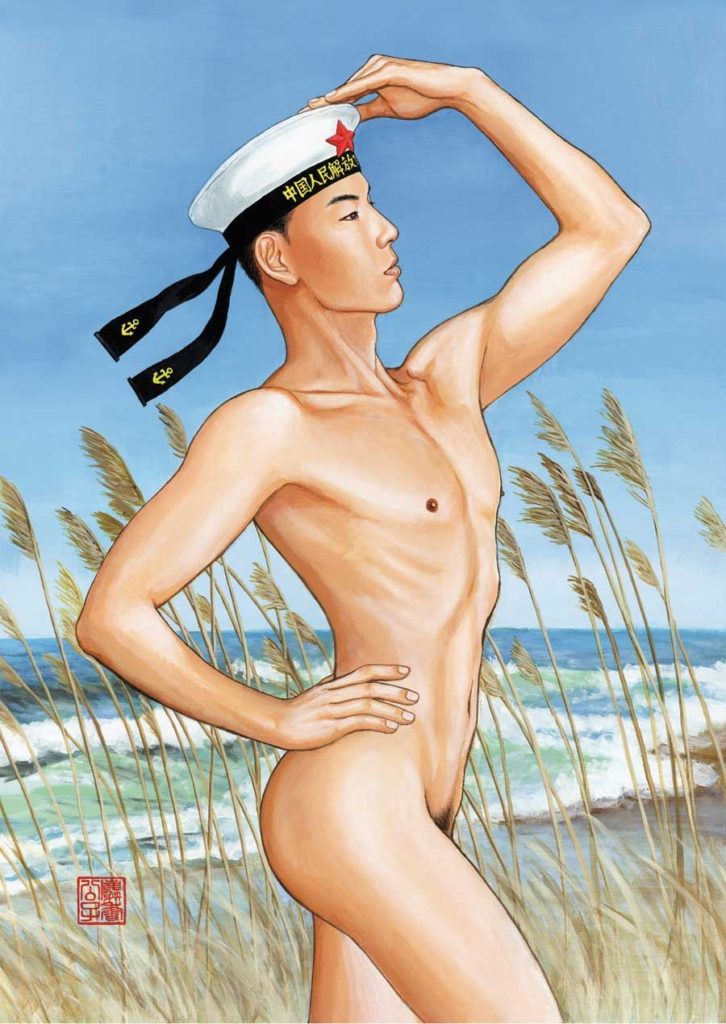

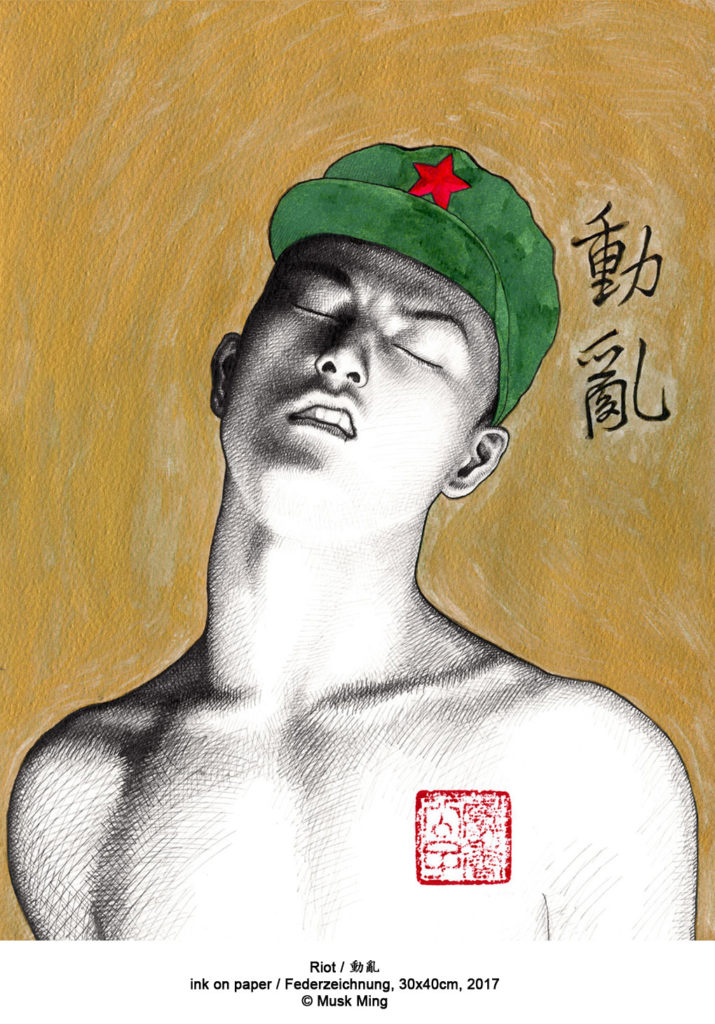

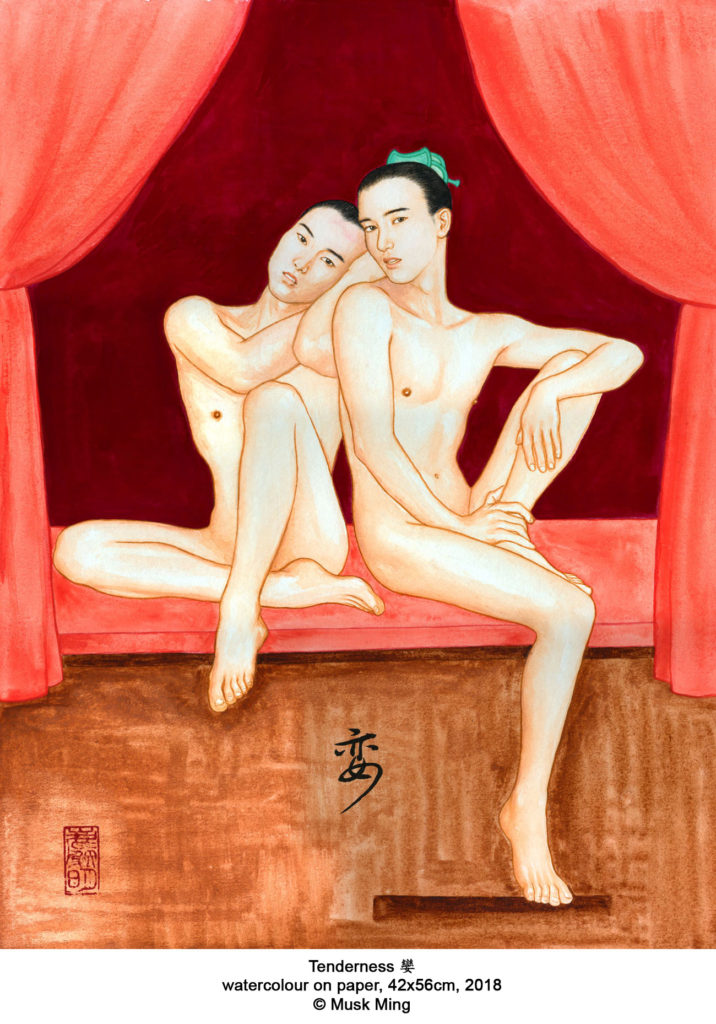

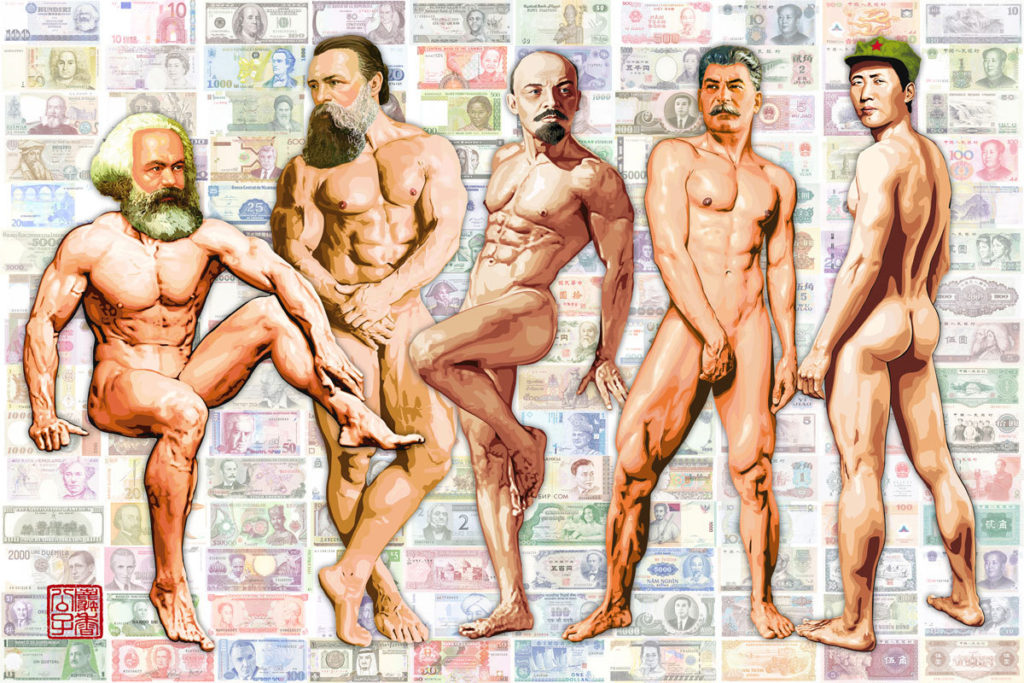

The Berlin-based Chinese artist Musk Ming introduces us to a world where social realism, the iconic homosexual aesthetic of “Tom Of Finland” and a spiritual beauty with Chinese characteristics are deeply intertwined. The men he portraits are objects of lust and transmitters of social commentaries at the same time, from tender PLA soldiers to slender male concubines hiding in forbidden cities to a muscular Mao Zedong showing us his naked backside. We talked with him about his childhood in a military compound, trouble with censorship, his life as a gay expat in Berlin and his glamourous musical side project.

Subtropical Asia: You were raised in a military compound, which might explain your attraction to young soldiers. But there is still a long way to go from an inner drive to the expression of an artwork. Where did your impulse come from to pick up a brush and create?

Musk Ming: I’ve been painting since I can remember and it actually seems natural to me to create with a brush. But as I got older, the themes of my paintings became different.

I spent my childhood and youth in said military compound. That’s where It dawned to me that the soldiers resemble the concubines in the “Grand View Garden” (大观园, a scenic interior landscape in the classic Chinese novel “Dream of the Red Chamber”), living in an artificial and isolated environment, even like some kind of Eden.

When I was a child, our textbook had a famous essay in it, titled “Who are the Most Beloved People?” about the Chinese People’s Volunteer Army (PVA). I felt that the “military brothers” I saw every day were “the most beloved” to me.

When did you decide to make them one of your artistic subjects?

Later, after graduating from college. At the beginning, it was more like a traditional Chinese painting style. But I also painted workers, peasants and soldiers in an old-school-propaganda way. When I think about it carefully, I might also be affected by the “People’s Liberation Army Pictorial”, a magazine that was common in my childhood home. But I cannot say that I have a general admiration towards soldiers, it’s more like a familiarity, and with the familiar I sense security. For me it also incorporates some kind of ascetic practice, a temple-like life.

Have you ever had problems in China with censorship because of the bold combination of political symbols and human bodies in a lustful, gay context?

I always have had difficulties with the cultural censorship in China. I haven’t exhibited my paintings there for many years. During the Beijing Olympic Games 2008, I had created a special painting, selected for the Olympic Art Congress. Just a few days before the exhibition, it was removed during the audit. And because of an interview I gave to the Chinese queer media, my official website can no longer be accessed normally in China.

Do you think a Western audience can get the sometimes very specific cultural nuances in your work? Or do they usually interpret your work from a completely different angle?

There was always a variety of understandings when it comes to my work. But especially during my early exhibitions, I often felt shocked by all kinds of strange and naive questions from a Western audience, but now I don’t care anymore. Whether it is seen from a rather shallow aesthetic point of view or a deeper cultural understanding: if I can evoke different views and understandings in different people, it shows at least that my work is not monotonous and one-sided.

Let’s take the poster for the Berlin exhibition “cult, superstition, das Kapital”, where we see the most famous socialist leaders, overly muscular and in the nude. As a Chinese I immediately see the sarcasm of how these figures are pulled from their high pedestal. On the other hand, you talked about your dissatisfaction with the Western understanding of communist forms as simple and crude. Can you tell us a little more about the views and implications of this exhibition and the poster?

It was in 2012, my first conceptual exhibition, which summed up a lot of the feelings I had gathered in Berlin over those years, and I tried a lot of different media, such as digital work, multi-material sculptures, performance art videos and so on. The poster was inspired by the political and economic textbooks of my middle school and university years, combined with the culture of fitness and consumption in an American Pop-art style. Although politics is complex, I feel that politicians are human too, and everyone is equal in terms of nudity. The exhibition was a breakthrough for me. Eight years on, I’m thinking about the opportunity to hold another new conceptual exhibition.

Why did you decide to move to Berlin? And what’s your life like there now? You used to say that “Berlin is cruel”…

I’ve been in Berlin since 2005. Berlin is a very suitable place for artists to live, there are so many crazy people here. I finally no longer feel that I’m special, in China it was rare for me to get a sense of “blending in”. Here I am completely free to create.

Berlin’s cruelty lies in its atmosphere of “no taboos” – it’s full of adult fairy tales, neither naive nor utopian, everything is naked and unabashed. From the realism of Käthe Kollwitz, to Christopher Isherwood, to David Bowie, who roamed around in Berlins underground in the 1970s… over the past decade or so, I’ve seen a lot of young and talented people coming to Berlin, full of ideals. In the end they were squeezed out of their beautiful vitality and disappeared. So the myth of the so-called “city of sin” is not a false statement….

We are also very curious about the time before you moved to Berlin. Could you come out already to family and friends?

Before 2005, I graduated from college, lived along an established path of “a good life” like most Chinese people. I worked in a company for a few years and didn’t come out of the closet. I was living a double life, a lost and chaotic period in hindsight. At that time I could only exhibit my works on some first generation local gay websites. The name “Muskboy” was created during that period, but the sites have long disappeared.

In addition to painting, you are also a singer, signed with a German music label. Personally, I think your music and music videos have a 80/90s retro vibe, some are even bit goth. What do you want to express through music and where you you get your inspiration from?

In terms of creativity, music was the most unexpected thing for me.

Through music I was able to express my own feelings and thoughts which cannot be directly conveyed through painting. It’s somewhat of a tribute to my high school and college days. Many of the lyrics are from old scraps of that time. In the end it gives me the opportunity to pretend that I’m still living in a parallel 80s/90s-universe…

In 2016, I returned to China for a tour. My previous experience in Germany was mainly singing cover songs and the audience was kind of old. The live music culture in China was fresh to me, and the audience was young. Singing my own Chinese songs to them was a completely different experience. And being on the road totally different from creating alone.

The Corona-epidemic is not over yet in Germany. Has it affected your life and artistic creation? What kind of works are you busy with recently?

The impact of the Virus on my life and artistic creation itself is not very big, because I usually work at home. However, due to the epidemic situation, my solo exhibitions and an art conference planned for this spring were cancelled or postponed.

I’ve been participating in many exhibitions over the past 15 years and I’ve always felt that exhibitions in galleries are very limited when it comes to visibility. That’s something I realized even more through this outbreak.

In recent years, I showed my work more and more on online platforms, from where I can get more instant feedback.

These days, I’m working on some canvas and paper paintings, and I’m also shooting and editing new music videos.

Musk Ming

Follow Musk Ming on Instagram

Like this content? Follow Subtropical Asia on Instagram